In 2003, just one year after professors Lewis Glinert and Alexander Hartov founded the Dartmouth Jewish Sound Archive, Theodore Bikel, the celebrated American actor, singer, and political activist who toured for decades as Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, wrote to them to request access.

"It's like having someone like Shostakovich suddenly write to you," recalls Glinert, a professor in the Middle Eastern Studies Program.

Two years later, a friend of jazz legend Ornette Coleman discovered the archive.

"He told us that Coleman had talked about the cantor Joseph Rosenblatt having 'one of the most amazing voices,' and said that if recordings could ever be found, he would love to hear him again," Glinert says. Coleman had lost his own recording during a move.

"We were thrilled to help provide Ornette Coleman with a recording of Joseph Rosenblatt!" Glinert says.

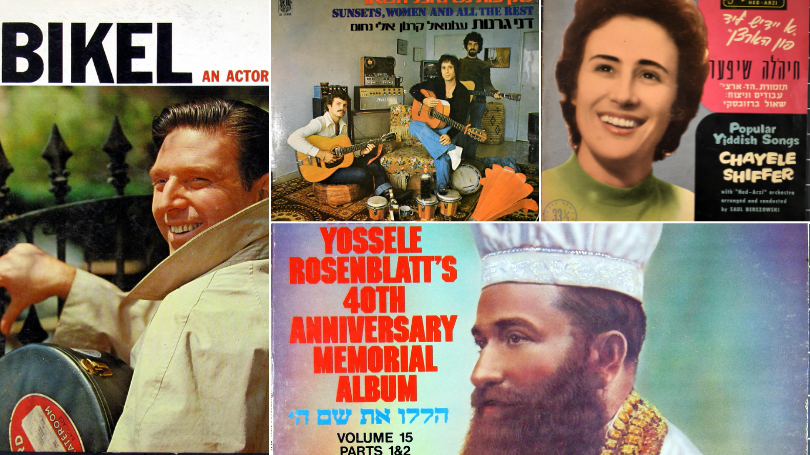

This spring, 21 years after the archive's modest launch, it will surpass 150,000 tracks dating back to the early 1900s, encompassing radio broadcasts, religious services, personal histories, Yiddish and Klezmer music, and more.

When Glinert and Harkov launched the collection in 2002, they never imagined it would grow into one of the largest archives of its kind, or that it would garner interest from people around the world.

The archive began when Hartov digitized hundreds of old records that belonged to his wife's uncle, who had hosted a Jewish radio show in the 1950s. Within months, The New York Times published a feature about it, which led to contributions of recordings from across the globe.

"People write to us from as far away as Poland, Australia, and Singapore," says Hartov, now a professor emeritus of engineering. "Not only scholars and broadcasters, but people from all walks of life who are curious about Jewish history. This often develops into their contributing records to the collection that we would not easily find in this country."

The archive experienced another growth spurt in 2018, when a collaboration was established with the Jewish Music Research Centre at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Among other enhancements, the partnership equipped the collection with biographical and musicological metadata that make its contents more accessible to researchers.

The database includes sound files, scanned images of record covers and labels, and details related to the recordings and their contents. Dartmouth community members can log in to the archive with their email credentials, and members of the public with scholarly or research interests can register for access. The collection can be searched by album, genre, language, occasion, or theme.

For each Jewish holiday, Glinert features a selection of recordings on the archive's homepage. For example, visitors this month will find a selection of songs and services related to the traditional Passover Seder, including a 1980 recording by the Israel Broadcasting Authority of Passover ceremonies affiliated with 16 ethnic groups in Israel.

Looking back, Glinert is especially moved by the many inquiries he and Harkov have received from non-Jews.

A young person in Mexico, for example, wrote to them a few years ago to request access to the archive, saying that he had always been interested in Jewish culture but was not near a Jewish community.

About 10 years ago, an American cultural attaché in Kyiv wrote saying he was trying to support Jewish culture in Ukraine. "He wasn't Jewish himself," Glinert recalls, "but he wanted access to our website."